by Michael Raspuzzi and Aldair Gongora

This time last year at a lab automation hack, one L6 engineer from Google led his team to win a lab automation hackathon with an orchestration layer for multiple agents with Sonnet 3.5. They were able to run through workflows in 1 day that previously would have taken teams 5-10x longer. We wanted to make sure that was a starting point for all hacks this year.

Now every one has access to tools like Claude Code and Cursor with these features baked in enabling real experiments to run on robots in 24hrs. This is a big deal for how more science can get done. Faster design and development of experiments. Easier onboarding for lab automation. This leads to more experiments from smaller teams.

In our more recent 24hr AI for Science hackathon in San Francisco, the top teams got cell data using Vibrio natriegens with projects like:

Pippin - A voice-controlled interface that self-optimizes liquid handling parameters. Talk to your robot, it tunes itself.

Protocol Monitoring - Phone camera + vision model watching the robot, flagging issues in real-time.

Closed-Loop Experiments - AI decides what to run next based on results, executes it automatically.

All shipped in 24 hours. The MCP was the foundation—once you can control the robot conversationally, the interesting stuff becomes possible.

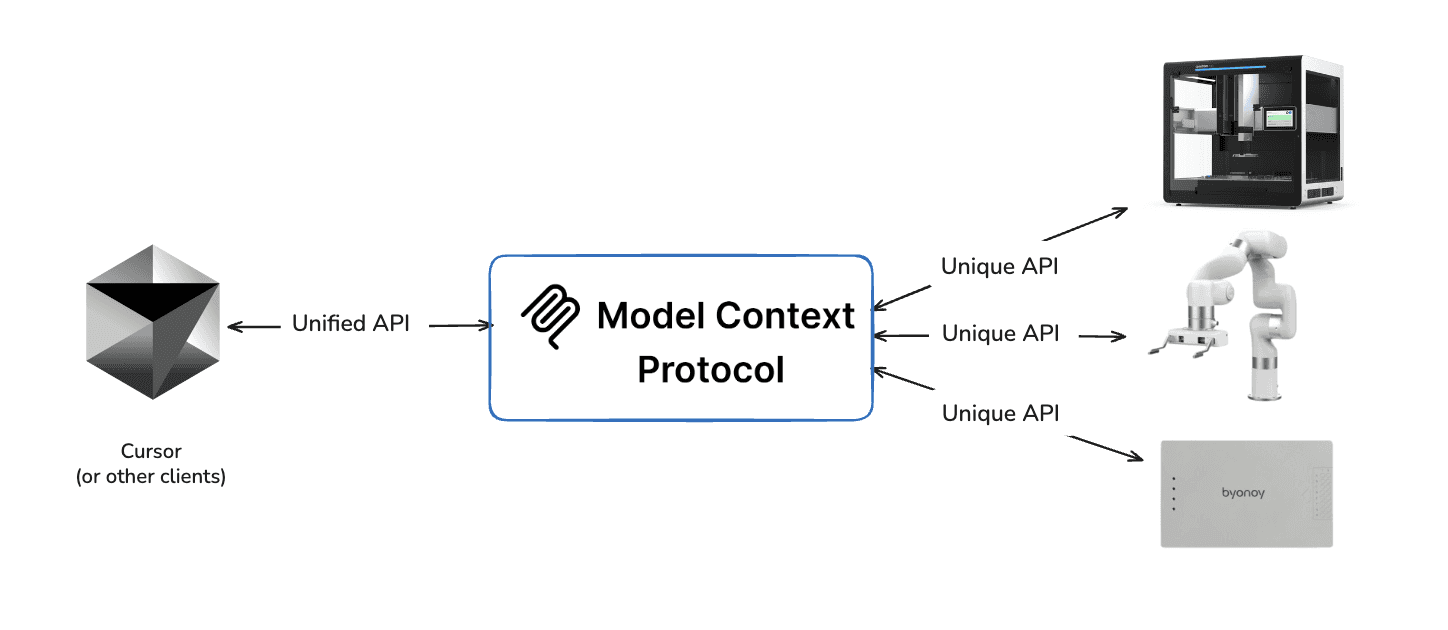

One invisible enabler of speed was Model Context Protocols (MCPs), which help large language models talk to tools. Many people think MCPs as software connectors, and we’ve seen them be more interesting as bridges to physical tools and infrastructure.

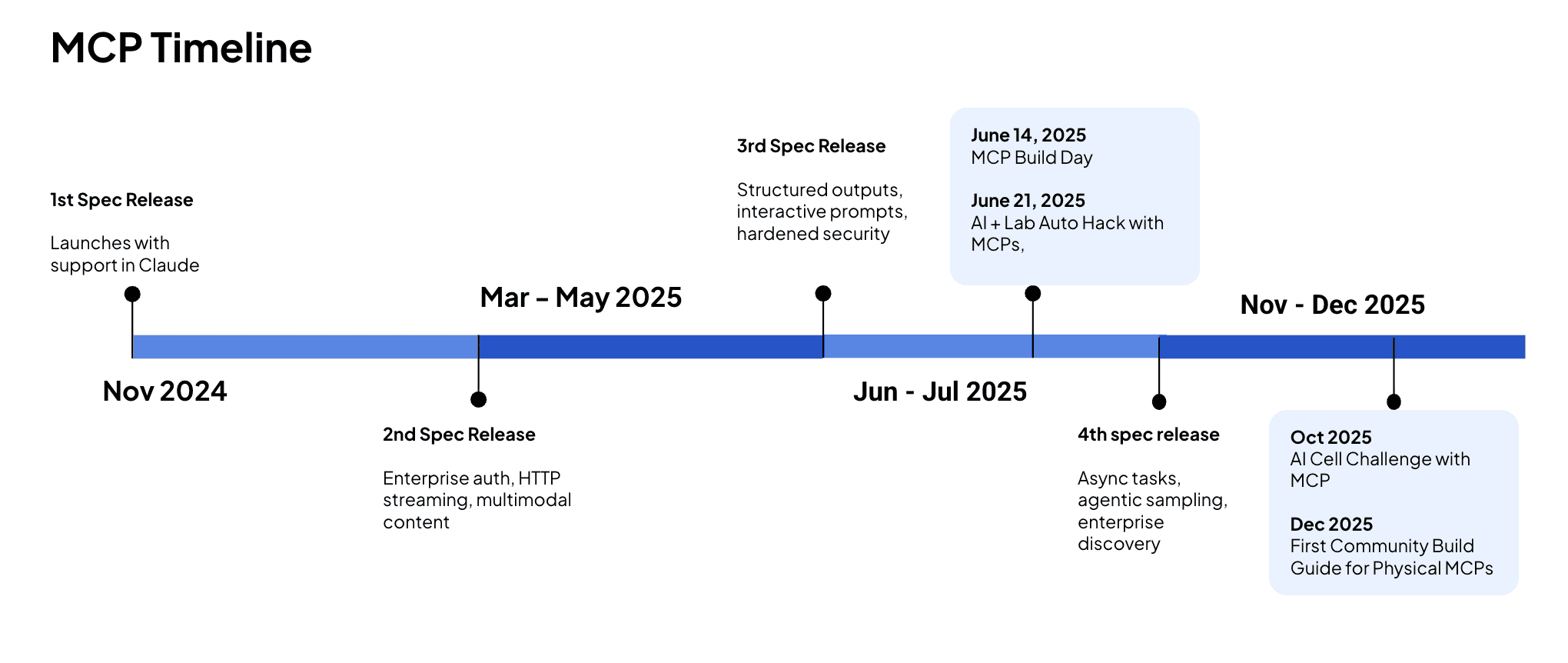

Anthropic donates MCP to Agent Foundation and timeline inspired here.

This guide will help you understand what MCPs are and how to build your own so that you can talk to your Opentrons Liquid handling robot in natural language.

What's an MCP and Why Should You Care?

Model Context Protocol is a standard way for LLMs to talk to external tools. Think of it like USB adapter for AI, where one protocol connects to many devices.

For lab automation, this matters because your robot already has an API. The MCP just makes it conversational. Instead of writing POST /runs/{id}/actions with {"actionType": "play"}, you say "start the run." Same result, now run in natural language.

Why Opentrons Flex?

Opentrons robots expose an HTTP API on port 31950. It's well-documented, battle-tested in real labs, and works with both the Flex and OT-2. If you can ping your robot, you can build an MCP for it.

What You'll Need

Node.js 18+

Opentrons simulator (or robot)

Claude Desktop

About an hour

The Architecture

Here's how the pieces connect:

Your MCP server is the translator. Claude says what it wants, your server makes the API calls, the robot moves. The robot doesn't know it's talking to an AI.

Building It

1. Set Up the Project

Create index.js:

2. Define Your Tools

Start with the basics. Here's a tool to check if your robot is alive:

3. Handle the Tool Calls

When Claude calls your tool, make the actual API request:

4. Run the Server

5. Connect to Claude Desktop

Add this to your Claude Desktop config:

macOS: ~/Library/Application Support/Claude/claude_desktop_config.json

Restart Claude Desktop. You should see "opentrons" in your available tools.

No Robot? No Problem—Use the Simulator

Don't have an Opentrons robot yet? Opentrons provides a software simulator that runs the exact same HTTP API on port 31950. Your MCP can't tell the difference between the simulator and a real robot.

Install Python 3.12

The simulator requires Python 3.12. We recommend using pyenv to manage Python versions:

Set Up the Simulator

You'll see output like Uvicorn running on http://localhost:31950. The simulator is now running.

Verify It's Working

You should see:

Test with a Protocol

Create a simple test protocol (test_protocol.py):

Important: Use p300_single not p300_single_gen2. The simulator runs with default pipette configurations—if you request a pipette model that isn't "attached" to the simulated robot, protocol analysis will fail.

Now ask Claude: "Upload test_protocol.py to localhost and create a run"

What Works in the Simulator

Feature | Status |

|---|---|

Health checks | ✅ |

Protocol upload & analysis | ✅ |

Run creation & control | ✅ |

Pipette commands | ✅ Simulated |

Module responses | ✅ Simulated |

Actual liquid transfers | ❌ No hardware |

Camera/vision | ❌ |

Alternatives

Skip the simulator entirely: The MCP includes documentation tools (

get_api_overview,search_endpoints) that work without any robot connection—useful for exploring the API first.Use Docker: If you have Docker installed, run

docker-compose up --buildfrom the opentrons repo root. Simpler setup, same result.

Adding More Tools

The health check is just the start. Here's what else you can add:

Protocol Management

get_protocols- List all protocols on the robotupload_protocol- Send a new protocol file

Run Control

create_run- Set up a protocol runcontrol_run- Play, pause, stopget_run_status- Check progress

Hardware

home_robot- Send axes homecontrol_lights- Turn lights on/off

Each tool follows the same pattern: define the schema, handle the request, make the API call, return useful output.

Making It Better

Some ideas if you want to explore MCP more.

Claude skills: Create agentic workflows with skills.MD files that reference the MCP.

More endpoints: The Opentrons API has ~80 endpoints. Modules, calibration, deck configuration—all available.

Error recovery: When something fails, have Claude analyze the error and suggest fixes.

Multi-instrument: Connect your plate reader, microscope, and liquid handler through one MCP.

Vision: Add a camera feed so Claude can see what the robot is doing.

Also, it’s important to note that the more MCP tools you have, the more context it takes up. So Anthropic has recommended coding APIs rather than MCPs alone for effective agent workflows.

Open Questions, Rough Edges, and What We’d Watch Next

Before we wrap, it’s worth pausing on the stuff that doesn’t fit neatly into a demo. This is the “read the comments” part of the recipe. Here are things you only learn once you actually try to run this in a real lab.

A few things we’d think about upfront:

1. What’s the Python (or your favorite language) version of this, really?

The examples here use JavaScript, but in practice a lot of lab automation stacks live in Python, and that changes the shape of things pretty quickly. The right starting point depends less on what looks nice in a demo and more on what your application is already built on and how you want to test MCPs without tearing everything apart.

If you’re controlling real instruments, odds are their APIs already speak Python. A concrete example is an Opentrons-style MCP implemented in Python, where libraries like FastMCP make it easier to wire agents directly into hardware control code.

The big takeaway: don’t just ask “can I build this?”—ask “what breaks first?” Pay attention to how your MCP server, your agent framework, and your instrument APIs actually interact, because that friction is where most real-world complexity shows up.

More here: Anthropic API 🤝 FastMCP Blog

2. One agent is fun. Multiple agents is where it gets real.

A single agent controlling a single tool is a great way to learn and that’s exactly what we showed here with one agent talking to the Opentrons MCP server. However, things change fast once you start imagining more than one agent in the loop.

Maybe one agent handles liquid handling, another watches data quality, and a third decides what to do next. Now you’re dealing with coordination, shared state, and new failure modes that just don’t show up in toy examples.

That doesn’t mean you should start with a full agent swarm, but it does mean it’s worth thinking ahead. A simple rule of thumb: sketch it out. Draw a rough hierarchy of agents, list which tools each one can touch, and think through how they hand work off to each other. That small bit of upfront clarity can save you a lot of debugging later.

Further reading: A Practical Guide to Building Agents by Open AI

3. How long can a task get before things fall apart?

Single, one-off actions are easy: run a protocol, take a photo, move a plate. The trouble starts when tasks stretch out such as long to-do lists, retries, interruptions, or chains of tool calls that all depend on the previous step going right.

At that point, it’s less about whether an agent can use a tool and more about how many tool-action pairs you’re asking it to manage before things get fragile. This really matters once hardware is involved. Every extra step is another chance for state to drift, assumptions to break, or timing to go wrong. In a physical lab, that can mean collisions, stalled runs, or damaged equipment. A good design habit is to ask: where’s the natural stopping point?

Break long tasks into smaller, check-in-friendly chunks, and give agents clear places to pause, verify, or hand control back before something expensive goes wrong.

More here: Measuring AI Ability to Complete Long Tasks

4. How do you know it’s actually better?

Benchmarks don’t need to be fancy, but they do need to exist. Once you start swapping models or letting agents touch real instruments, it’s worth asking what “better” actually means for your setup.

Is the agent faster? Does it make fewer mistakes? Does it reduce the number of times a human has to step in and fix something?

It’s tempting to jump straight to full agent-driven instrument control, but a little measurement goes a long way. Try the same task with different models. See which one handles long instructions better, which one recovers more gracefully from errors, and which one you’d actually trust near expensive hardware. In practice, this often leads to mixing and matching where you might prefer one model for planning and another for execution.

5. Not every agent plays nicely with MCP (and that’s okay).

One thing you’ll run into pretty quickly is that not every model or SDK is a natural fit for MCP-style tool use. Some agents just don’t support tool calling out of the box, and that’s not a failure. It’s a design constraint. Take smaller models like Gemma3n.

They can be fast and useful, but you may need to do extra work, like prompting the model to emit structured JSON that maps to predefined functions so it can interact with APIs or code in a grounded way. In other cases, the friction just isn’t worth it. This is where matching matters.

The model, the agent framework, and the SDK all need to agree on how tools are called and how state is handled. It’s also worth thinking about modality early. Does your agent need images, language, audio, or some mix of all three?

Choosing tools and models that naturally support what you need will save you a lot of debugging, and sometimes the right move is to adapt your setup or walk away and pick a better-aligned stack.

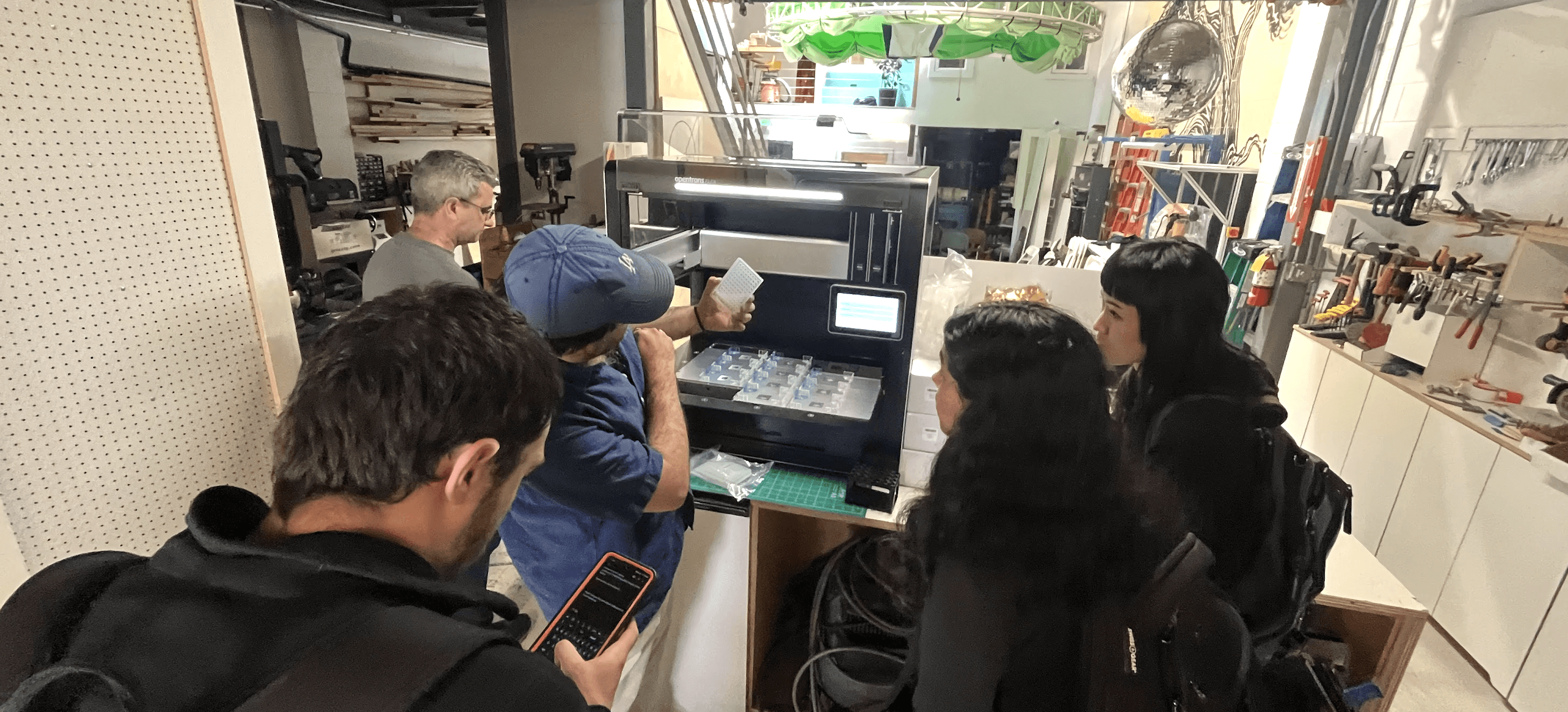

You can just build things to try them out

Physical MCPs are being built right now at weekend hackathons by people who want to try something. You don’t need special access in a lab.

The tools are ready. Your robot already speaks HTTP. Claude already speaks MCP. You're just connecting them.

The full code is here (h/t Gene for building this Opentrons MCP). Clone it, modify it, build something we haven't thought of yet.

The only way to keep up with what’s possible is to build with it, and we find building is better in community.

👉Sign up for AI for Science Hack + Build updates here.

Thank you to our partners!

Gene for community MCP (original repo here)

Luis and the Bay Area Lab Automators for co-hosting builds in the community

Shanin, Homam, Krishna, and the whole Opentrons team for supporting builds like this

About writers

Michael Raspuzzi is founder of Worldwide Studios, where he enables people to build with the latest across AI, robotics, and applied science in community hacks and programs.

Aldair Gongora is a staff scientist at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, where he builds self‑driving labs that combine automated experimentation and machine learning to accelerate materials discovery and design.

Want to support the next community hack or build? Reach out.